NIL (Name, Image, and Likeness) refers to a person’s legal right to control how their image is used. Before 2021, college athletes were prohibited from receiving any NIL money or endorsements from brands or businesses. The Knight Commission (focusing on athletic growth through name, image, and likeness) saw this as unfair for the colleges because it was too rewarding for the institute and the athletes.

Unfortunately for athletes before the NIL deal got passed, the NCAA would not compensate their athletes by giving them any sort of incentives. For example, in 2005, USC running back, Reggie Bush, won the Heisman Trophy. After the NCAA conducted research on Bush, in 2010 they discovered that he was receiving improper benefits from the school. Because of Bush’s and the university’s actions, the NCAA football committee took away his Heisman trophy.

On July 1, 2021, the NCAA approved NIL policy to allow student-athletes to monetize their NIL. This meant that college athletes could receive endorsements and advertising money from business deals and partnerships.

Fortunately for Bush, on April 24, 2024, the committee reinstated the 2005 Heisman Trophy to the former Trojan because they realized his illegal earnings from the university did not affect his position on the final standings of the Heisman race.

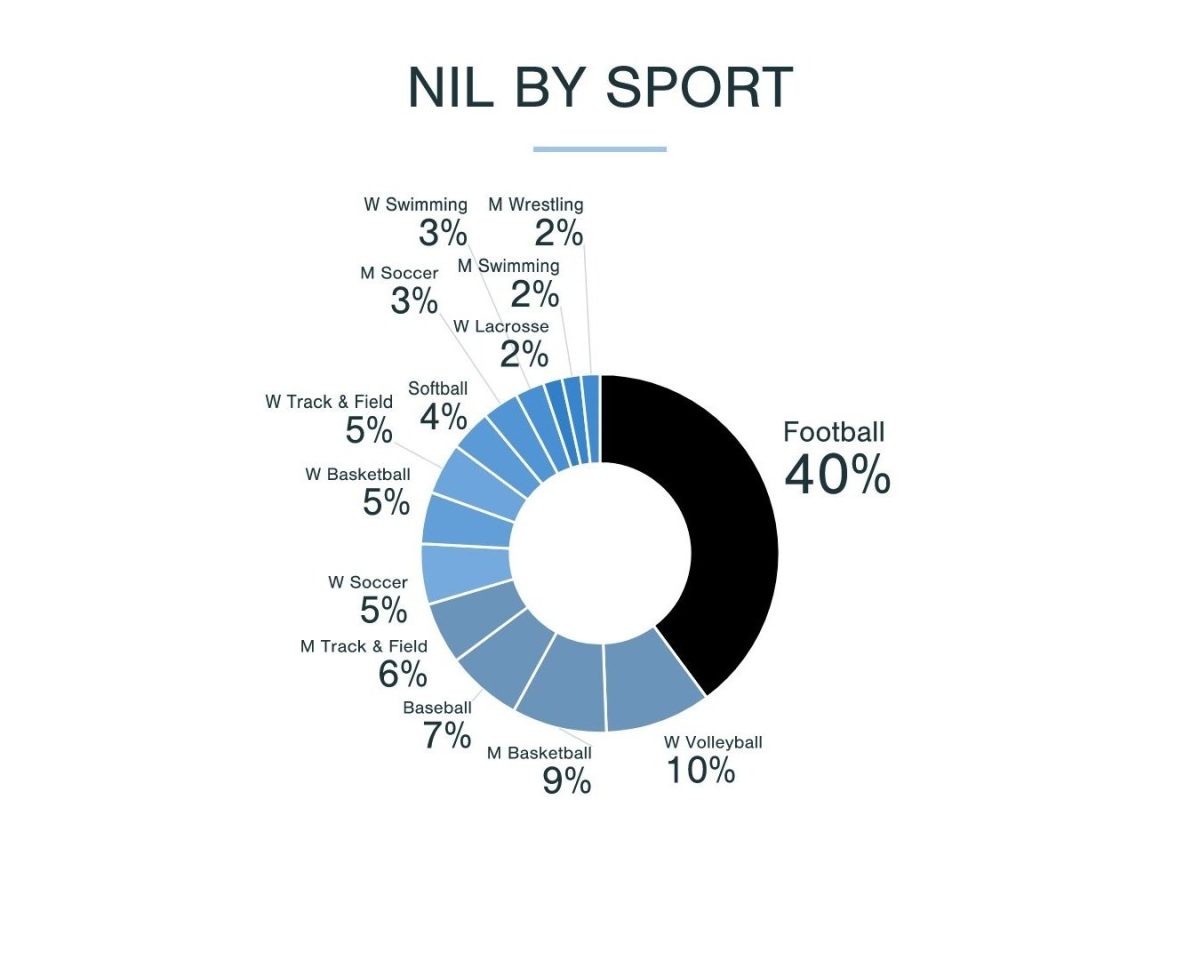

The average NIL income for student athletes is between $1,000 and $10,000 per year, but top athletes such as 19-year-old University of Texas quarterback Arch Manning, and 23-year-old University of Colorado quarterback Shedeur Sanders, generate more than $6.2 million total from deals and brand partnerships in just one year. An even more impressive story is now 18-year-old freshman (17 during the ‘24-’25 CFB season) Ryan Williams, having a market value of over $2.7 million in NIL valuation.

Because college sports are a business, smaller schools have a smaller market value. These power four and five schools have more money to distribute to student athletes than smaller schools with a lower attendance rate so it creates an unfair advantage among competition. These NIL endorsements sway athletes from school to school when making decisions for their collegiate career. Ultimately causing these athletes to hit the transfer portal.

As of 2024, the University of Alabama had an NIL value of $13 million among all athletes, while a slightly smaller school such as Mississippi State had a budget of only $6.48 million. This is unfair because they may be in the same conference as bigger schools, but they don’t generate the same value. And for non-power five schools it’s even harder because they don’t get the public attention. This attention brings in even more money and introduces different press releases that the athlete can advertise. Therefore the revenue goes to other schools because of the athletes that have committed there.

When high school athletes are deciding which college to pick, nowadays they turn their head towards the money instead of making their decision based on the location, coaching, or culture of the school. These colleges persuade young athletes to come to their college to help profit even more money for the university as a whole.

Some of these athletes also make more money through their NIL deals while in college than they would in the pros. This sways their decision to stay in college for another year or two. These schools end up bringing in more money, ultimately increasing their NIL budget for the years to follow. For example, Caitlin Clark made a total of $3.1 million in her college career from NIL deals while playing women’s basketball for the Iowa Hawkeyes. In 2023, Clark decided to stay at Iowa and play another year, and many speculated that a reason for that was because of the revenue she was making while still in college. To emphasize this, Clark will make $78,000 in her 2025 WNBA season, which is a penny compared to her NIL endorsements.

This market of name, image, and likeness has completely changed college sports to be more of a business instead of a production for the growth of upcoming athletes. This negatively affects college athletics as a whole, forcing players to love the money more than the game.