For new students, seeing “HALE” at the bottom of PowerSchool for the first time can be confusing, especially since it’s not an actual class at ENHS.

High Ability Learner Education (HALE) is the accelerated learning program in the Elkhorn Public School district.

“We’re supporting students in a way that makes sense for each individual student,” HALE coordinator Molly Erickson said. “Part of a gifted program is providing opportunities for students that are going to help them grow and learn. . . Much like a special education teacher would do for a student, I would do the same for my gifted students.”

HALE students are selected starting in third grade, and curriculum modifications begin in fourth grade. These students are pulled out of class for a few hours where they read different books, make dioramas, and work on complex math problems.

“I feel like I would’ve been a lot more bored in the regular classroom versus what I was doing [in HALE],” Senior Nolan King said.

ENHS students have mixed experiences in the elementary HALE classroom, but many found it engaging and enjoyable.

“I’m not good with slow-paced things. I get really bored, and then I won’t pay attention,” sophomore Ady Tuttle said. “But if it’s more fast-paced, I feel like I have to pay attention; I don’t have a choice. That helps me a lot with getting work done.”

On the other hand, some found the program inconsequential and felt the extra work didn’t help in core classes.

“I remember thinking in middle school that it was just a lot of extra work without learning anything extra,” senior Amina Teri said. “I think it could’ve been more challenging, and I guess more personalized. I know it’s difficult to do that for so many students, but I think you can play to people’s strengths more easily.”

“I didn’t really like [HALE],” sophomore Will Swagler said. “It’s not the fact that it wasn’t challenging, it’s just that what we were doing couldn’t be applied to many things.”

In high school, the impact of HALE diminishes as the focus shifts to managing academic clubs like Quizbowl and Academic Decathlon rather than altering curricula.

“I don’t know that we’re doing the best we could be at the high school level,” Erickson said.

Some HALE students notice the negative effects of their elementary and middle school HALE experience once they reached high school.

Tuttle notes a similar experience emphasized by her time in the Omaha Public School (OPS) district. She transferred to Elkhorn North Ridge Middle School in the middle of sixth grade.

“I always felt that when I went to OPS, the classes were too easy, too slow,” Tuttle said. “I never learned how to properly study. I never learned how to properly go over notes. Then I get put into Elkhorn, and suddenly everything’s just a little bit harder. . . It makes me a little bit upset that I was never taught how to properly study.”

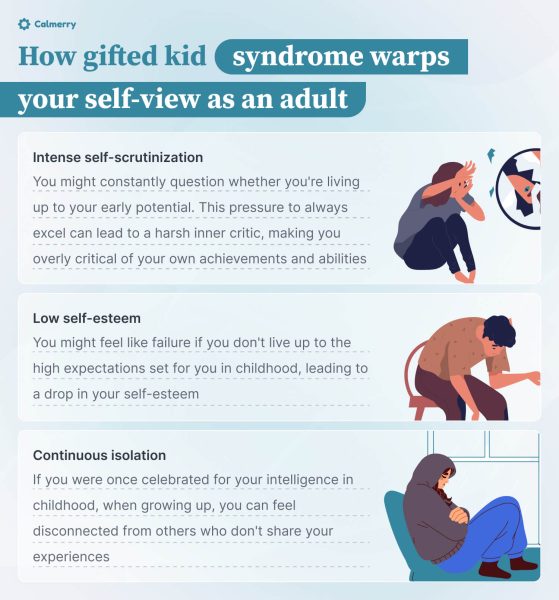

Many HALE students experience Gifted Kid Syndrome.

This is a growing phenomenon. Kids who are praised and called “gifted” when they are young get comfortable with effortless success. Later, whether that’s in middle school, high school, or college, they fall behind their peers and experience Gifted Kid Burnout.

Symptoms of Gifted Kid Syndrome include: low motivation, perfectionism, critical self-analysis, high expectations for themselves, dislikes for things they aren’t immediately good at, and procrastination. They also struggle with: deadlines, failure, and rejection.

“Most of my gifted students aren’t failing their classes, but we want to make sure that you’re being challenged,” Erickson said. “School should be a place where you enjoy going and learning, and you feel like you’re getting the same experience as everyone else. So, if you’re trudging through your day bored and doodling in class or reading a different book because you already know all the material, we’re not doing our job.”

Gifted students’ high expectations for themselves tend to cause overcommitment to classes and clubs.

“A lot of my homework has to be done last minute, like in the morning or late at night, but ultimately I get my stuff done,” Teri said.

Additionally, the National Institutes of Health have found that gifted kids are reported to have more mental illness and neurodiversity.

“There are times when some students really want to do well, but they forget to be a kid,” Erickson said. “You don’t have to have all ones. If it’s a really hard class, and your grade dips a little, there’s still going to be scholarships and college opportunities.”

Despite the good intentions behind gifted programs, a reevaluation of the approach may be necessary.

“I don’t like the idea of collecting a bunch of kids and saying ‘You’re smart, you’re better than other people,’ giving them thoughts like, ‘I don’t have to study,’” Tuttle said. “My mindset used to literally be: I’m better than these people; I’m smarter than the other kids― It was not a good mindset to have.”